Without JCPOA, Iran to Be on Much Higher Position

In an exclusive interview with The Associated Press, Ali Akbar Salehi stressed

Iran would be guided by "prudence and wisdom" when weighing whether to abandon

the deal if European nations fail to protect it from Trump.

Salehi dismissed out of hand the idea of caving to American demands to

renegotiate the accord.

"Yes, we have our problems. Yes, the sanctions have caused some problems for us.

But if a nation decides to enjoy political independence, it will have to pay the

price," Salehi said. "If Iran decides today to go back to what it was before,

the lackey of the United States, the situation would" be different.

Salehi heads the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, whose Tehran campus

encompasses a nuclear research reactor given to the country by the U.S. in 1967

under the rule of the shah. But in the time since that American "Atoms for

Peace" donation, Iran was convulsed by its 1979 Islamic Revolution and the

subsequent takeover and hostage crisis at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran.

Iran long has said its program is for peaceful purposes, but it faced years of

sanctions.

The 2015 nuclear deal Iran struck with world powers, including the U.S. under

President Barack Obama, was aimed at lifting those sanctions. Under it, Iran

agreed to store its excess centrifuges at its underground Natanz enrichment

facility under constant surveillance by the UN nuclear agency, the International

Atomic Energy Agency. Iran can use 5,060 older-model IR-1 centrifuges at Natanz,

but only to enrich uranium up to 3.67 percent.

That low-level enrichment means the uranium can be used to fuel a civilian

reactor. Iran also can possess no more than 300 kilograms (660 pounds) of that

uranium. That's compared to the 100,000 kilograms (220,460 pounds) of

higher-enriched uranium it once had.

Salehi spoke to the AP on Tuesday about Iran's efforts to build a new facility

at Natanz that will produce more-advanced centrifuges, which enrich uranium by

rapidly spinning uranium hexafluoride gas.

The new facility will allow Iran to build versions called the IR-2M, IR-4 and

IR-6. The IR-2M and the IR-4 can enrich uranium five times faster than an IR-1,

while the IR-6 can do it 10 times faster, Salehi said. Western experts have

suggested these centrifuges produce three to five times more enriched uranium in

a year than the IR-1s.

Building the facility doesn't violate the nuclear deal, and Salehi said Iran

does not have a plan for mass production of advanced centrifuges.

"This does not mean that we are going to produce these centrifuges now. This is

just a preparation," he said. "In case Iran decides to start producing in mass

production such centrifuges, (we) would be ready for that."

Salehi suggested that if the nuclear deal fell apart, Iran would react in

stages. He suggested one step may be uranium enrichment going to "20 percent

because this is our need." He also suggested Iran could increase its stockpile

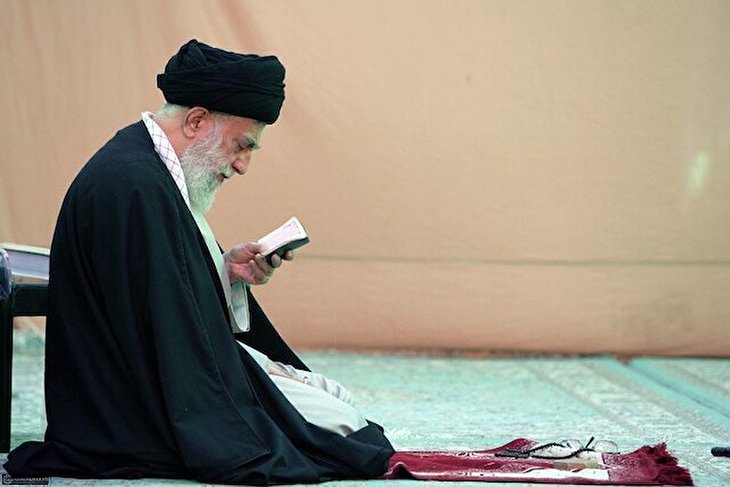

of enriched uranium. Any withdrawal ultimately would be approved by Leader of

the Islamic Revolution Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Khamenei.

While the UN repeatedly has verified Iran's compliance with the deal, Trump

campaigned on a promise to tear it up. In May, he withdrew the U.S. in part

because he said the deal wasn't permanent and didn't address Iran's ballistic

missile program and its influence across the wider Middle East. But Trump

meanwhile has tweeted he'd accept talks without preconditions with Tehran.

Asked what he personally would tell Trump if he had the chance, Salehi chuckled

and said: "I certainly would tell him he has made the wrong move on Iran."

"I think (Trump) is on the loser's side because he is pursuing the logic of

power," Salehi added. "He thinks that he can, you know, continue for some time

but certainly I do not think he will benefit from this withdrawal, certainly

not."

In the wake of Trump's decision, however, Western companies from airplane

manufacturers to oil firms have pulled out of Iran. The rial, which traded

before the decision at 62,000 to $1, now stands at 142,000 to $1.

Despite that, Salehi said Iran could withstand that economic pressure, as well

as restart uranium enrichment with far more sophisticated equipment.

"If we have to go back and withdraw from the nuclear deal, we certainly do not

go back to where we were before," Salehi said. "We will be standing on a much,

much higher position."

The Stuxnet computer virus, widely believed to be a joint U.S.-Israeli creation,

once disrupted thousands of Iranian centrifuges.

A string of bombings, blamed on the Zionist regime, targeted a number of

scientists beginning in 2010 at the height of Western concerns over Iran's

program. The occupying regime of Israel never claimed responsibility for the

attacks, though Israeli officials have boasted in the past about the reach of

the regime’s intelligence services.

"I hope that they will not commit a similar mistake again because the

consequences would be, I think, harsh," Salehi warned.